You Can’t Do That at a Funeral

Andy brushed a curled brown lock from his forehead, surreptitiously mopping his brow at the same time. It’s not a sin to sweat in church, he reminded himself; with countless confessions, weddings, and conscience-stabbing sermons that had taken place under this towering ceiling, he certainly wasn’t the first to perspire. Still, the best friend of the dearly departed was visibly uncomfortable, and more than a little aware that fear of public speaking ranks higher than fear of death. It didn’t help that it was April in Toronto, and while it was minus eight degrees Celsius outside, the inside of the spacious church was heated to a temperature more suited for souls in eternal torments. “I’m a little nervous,” Andy explained. “The last time I was here, they threw water on me, as I recall.” He made odd little sprinkling motions with his fingertips. Most of the audience sat silently, waiting for him to continue, but a few laughed politely. Nothing wrong with a little polite laughter. The man being remembered had, after all, proclaimed himself “The kind of guy that laughs at a funeral.”

“Finn Tyler led life to the fullll…” was how his eulogy began. He dragged the word out a few too many l’s, and then giggled nervously. It was a quick, high-pitched laugh; he covered it with a vigorous throat-clearing, and the family and friends gathered at Metropolitan United on Queen Street sat silently, many holding their breath.

“My friend,” he began again, “Had a huge heart.” He stared at his hands as if they were moving with a will of their own, sweeping up and making a vast shape. “I mean, huge! Like… like, all of him!” Andy pointed needlessly at the open coffin in front of him. The two thousand dollar one taking up a third of the stage, the one you couldn’t miss if you tried. Its occupant, the 6 foot 8, 350-pound former rugby player, stylishly reposing in a striking Egyptian blue suit was hard to miss as well. “What you folks don’t realize,” Andy said, clearly not working from the notes scrawled on the creased paper in front of him, “is that he’s folded in half inside there!” His finger stabbed the air, pointing down at the huge man sharing the platform with him. “God, I hope the pallbearers have a good chiropractor,” he added. Andy’s eyes were wide, giving him the appearance of a man in shock, whose body and voice were both conspiring against him. Someone laughed softly, and his nervous chuckle came out again, echoing in the huge neo-Gothic church.

Before things got away from Andy, he figured he’d start at the start. Which turned out to be the beginning of the end. “Finn Robert Tyler was born on the eighth of July… a sudden snort escaped his lips, “And the ninth, as a matter of fact. AND the tenth.” A sound of many sharp intakes of breath echoes now. “Finn’s Mom,” he nods in her direction, “Calls him each year, and says, ‘Happy birthdays, you big pain in the ass.’” You can say “ass” in church, it’s a Biblical term.

Canadians have a reputation of being polite, to a fault, even. Case in point, the silently fidgeting crowd, feeling imaginary splinters from the uncomfortable pews. Torn between the urge to laugh supportively at the man embarrassing himself, and to tactfully protest the obvious inappropriateness. Silence won out, and no doubt a handful of supplications went heavenward that Andy might return to material more suited to the somberness of the occasion. It was not to be.

Andy’s shoulders did a combination of shuddering and shrugging, as if he sensed that the saints high on the wall behind him were glaring at him in righteous indignation, the only anger appropriate in this sacred venue. Against all logic and common decency, he soldiered onward. “I mean,” he blurted, “can you not see that coffin he’s in?” He pointed it out again, clearly mindful of the seeing-impaired. “Eighty-seven inches long,” he recited, “Thirty-one inches wide. Two hundred and twenty pounds! Why, that’s bigger than the hearse!” A simultaneous hiss and gasp from the crowd made him pause for just a second. “We’ll have to bury it in the Thunder Bay Canyon – if it even fits!”

Andy went on for several more long and painful minutes, the crowd still too polite to interrupt, still praying that he might get back on track. But his train of thought was barreling fast and uncontrolled, a wreck was coming, and no one could look away. Except perhaps, the pious figures in stained glass. The only trinity present on this day was the unholy combination of poor timing, poor delivery, and the most unfunny jokes. It could be best described with a single word – Hilarious.

Andy saved what was arguably his worst for last, announcing the post-funeral gathering at the Swiss Chalet a few kilometers up the street. “There’ll be an all-you-can-eat buffet,” he concluded, but not before addressing the giant in the coffin one last time. “Not all you can eat.” It was too much.

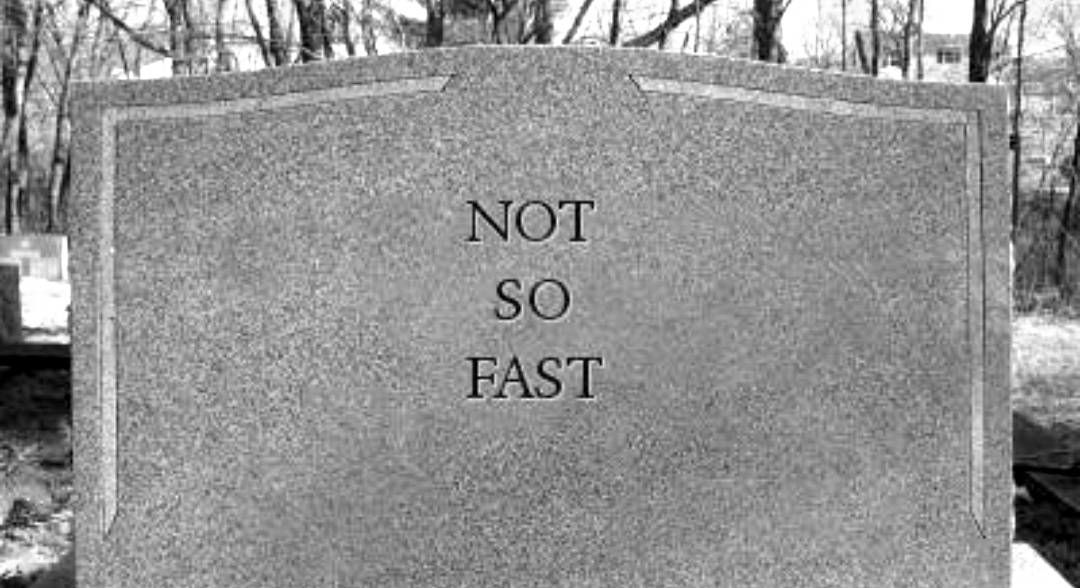

My shoulders started to shake, and I knew what was coming. Spasms signaled imminent eruption. I took a deep breath, knowing there was no dam powerful enough to hold it all back. And I laughed. Large, like everything I do. I’m a huge man, as Andy’s been saying. The Metropolitan boasts the largest pipe organ in Canada, one of the largest in the world, in fact. But the blast of laughter I let out would easily have drowned it out. My blue suit tore in three places as I sat up suddenly. And that, apparently, just isn’t done at a funeral.

END